Rare cardiovascular and pulmonary disease

Developing pioneering treatments for high unmet medical needs

Rare cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases are a diverse group of conditions that affect the heart, blood vessels, and lungs. These conditions are often difficult to diagnose and manage, and in many cases, there are limited treatment options. Cereno Scientific has a long-standing commitment to advancing treatments in the cardiovascular disease area, the indications particularly relevant to the company pipeline are further presented in this section.

Although each rare disease affects relatively few people, together they represent a major global health challenge. There are an estimated 6,000–8,000 different rare diseases, and up to 6% of people worldwide may be affected.1 This translates to about 30 million people in Europe and between 260–450 million people affected worldwide.2 Even though these diseases are individually uncommon, many of them have no effective treatments and can seriously impact a person’s quality of life.

In the cardiovascular field, rare diseases such as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) present unique challenges in both diagnosis and treatment.

Similarly, rare pulmonary diseases encompass a broad range of conditions. Most of these are chronic (long-lasting) and idiopathic (without a known cause). While some are limited to the lungs, others have a systemic origin or affect multiple organs, for example, pulmonary hypertension due to interstitial lung disease (PH-ILD) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

Despite recent advances, most available treatments are symptomatic or supportive, rather than targeting the disease itself. A few newer therapies have been approved in recent years, but these are often associated with significant side effects. This underscores the ongoing need for effective treatments that not only target the disease itself but are also well-tolerated and safe.

PAH

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH)

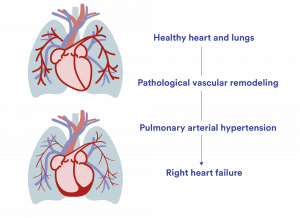

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare, progressive disease that affects the blood vessels in the lungs, leading to high blood pressure in the pulmonary circulation. In most cases, the cause is unknown. The disease is marked by thickening and narrowing of the small arteries in the lungs, including the development of characteristic plexiform lesions, which restrict blood flow from the right side of the heart to the lungs. Over time, these changes, combined with increased tissue scarring (fibrosis), reduce the elasticity of the blood vessels and increase resistance to blood flow. This process, known as vascular remodeling, raises the pressure in the pulmonary arteries and impairs circulation. In later stages, small blood clots (thromboses) may form locally, further worsening the condition. Ultimately, most patients develop right heart failure as the heart can no longer cope with the strain, which leads to death for most patients with PAH.

As a patient progresses in their PAH disease, the right heart and blood vessels in the lungs are increasingly strained and restricted until the heart gives up. Often only a few years after diagnosis.

PAH's annual global impact

- Approx. 80 000 people with PAH in US and EU

- Approx. 9 500 death in US and EU

- Around $3.1Bn is the societal economic cost in the US

- Around €2Bn is the societal economic cost the EU

Understanding right heart failure in PAH

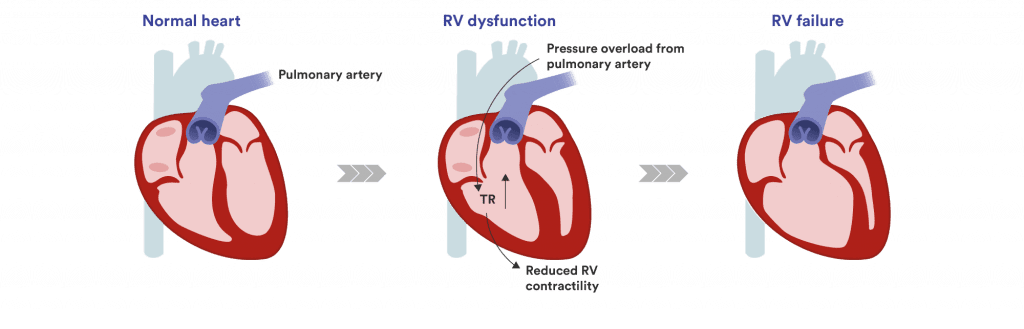

As pulmonary vessels become narrowed and stiff, the right side of the heart, especially the right ventricle, must work harder to pump blood through the lungs. This extra strain can cause the heart's tricuspid valve to leak (tricuspid regurgitation), leading to fluid build-up, enlargement of the right ventricle, and reduced pumping efficiency. As illustrated below, this vicious cycle of pressure and overload weakens the heart over time, often resulting in right heart failure, the most common cause of death in patients with PAH.

Understanding right heart failure: Over time, PAH causes tricuspid regurgitation (TR) leading to the right ventricle (RV) to weaken until it fails.

Significant impact on patient’s lives

PAH significantly affects patients’ quality of life. Common symptoms include shortness of breath, fatigue, chest pain, swelling, fainting, and heart palpitations. These symptoms often limit daily activities and can severely impact physical, mental, and social well-being. According to an ongoing global survey supported by the Pulmonary Vascular Research Institute (PVRI), most PAH patients report that the disease greatly affects their day-to-day life.

Main burden according to PAH patients:

- 74 % report negative impact on employment

- 54.5 % are disabled due to pulmonary hypertension (PH)

- 60 % struggle to walk short distances and climbing stairs

PAH is more common in women, particularly between the ages of 30 and 60.5 The median age at diagnosis ranges from 53 to 69 years.6 Globally, an estimated 192,000 people are living with PAH, with roughly half of those cases found in the US and Europe.

Current treatment landscape and unmet need

PAH is a severe, debilitating condition that worsens over time and does not improve on its own. Without treatment, the average life expectancy is 2.5 years; with current standard therapies, this increases to approximately 7.5 years.7 There is currently no cure for PAH, aside from lung transplantation, a procedure that many patients are too ill to undergo.

The current standard of care includes vasodilator medications, which help relieve symptoms and may moderately slow disease progression when used in combination with supportive therapies. However, these treatments do not reverse the disease and are often associated with significant side effects, especially in patients with other health conditions. The recent approval of sotatercept (Winrevair™, Merck) marks a new development in the field, but its role in long-term treatment is still being evaluated.

Given the limitations of existing options, there is a clear and urgent need for new therapies that are not only safer and well-tolerated but also modify the disease itself—addressing the underlying mechanisms of PAH to enhance and extend patients' lives.

Treatment goals and how progress is measured

The primary goals in treating PAH are to halt disease progression, improve symptoms and physical capacity, and reverse vascular remodeling. Ultimately, the aim is to enhance quality of life, improve patient function and extend survival utilizing disease-modifying treatments.

Progress is typically measured by:

- Risk scores, such as the REVEAL risk score

- Functional class, such as NYHA/WHO, which reflects a patient's physical capacity and symptom burden

- Hemodynamic parameters, including mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR)

- Together, these indicators help guide treatment decisions and assess how well therapies are working over time.

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs)

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are a broad group of disorders that cause scarring (fibrosis) in and around the lungs' air sacs (alveoli) and airways. The lung interstitium—the space between the air sacs and the small blood vessels— contains connective tissue that plays a vital role in gas exchange. When you breathe, oxygen passes through the alveoli and interstitium into the blood, while carbon dioxide moves in the opposite direction to be exhaled.

When scarring develops, the lungs become stiff and lose their ability to transfer oxygen efficiently, making breathing increasingly difficult. Over time, this can severely impact a patient's ability to perform everyday activities and significantly reduce quality of life.

A major factor influencing survival in ILD patients is the development of pulmonary hypertension (PH) secondary to pulmonary fibrosis. Pulmonary hypertension is increasingly recognized as a key complication in fibrotic lung diseases and may become a cornerstone of care for these patients. Among patients with pulmonary fibrosis referred for lung transplantation, pulmonary hypertension is present in approximately 25% of cases.

Pulmonary hypertension in ILD (PH-ILD) is associated with worse outcomes and significantly higher mortality. Studies show that patients with ILD who develop pulmonary hypertension have a three-year survival rate of only 32%, underscoring the severe impact of this complication.

Epidemiology and Common Forms of ILD

The global prevalence of ILDs is estimated to range from 6.3 to 71 cases per 100,000 people, reflecting differences in diagnostic practices and definitions across studies

Among the different forms of ILD:

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most common, accounting for about one-third of ILD cases.

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis represents approximately 15% of ILD cases.

- Connective tissue disease-associated ILD (CTD-ILD) accounts for around 25% of cases.

Each of these conditions shares the common problem of lung fibrosis but differs in cause, progression, and treatment approaches. Regardless of type, fibrosis and the potential development of pulmonary hypertension remain major contributors to poor outcomes in ILD patients.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease (ILD) that causes gradual scarring of the lungs, leading to a steady decline in lung function. Patients typically experience symptoms such as a severe dry cough, fatigue, and increasing shortness of breath with physical activity (exertional dyspnea). Over time, progressive scarring damages the lung tissue (parenchyma) and disrupts normal gas exchange, eventually resulting in respiratory failure.

The median age at diagnosis is 66 years, and men are more commonly affected than women.

The estimated prevalence of IPF is 5.67 per 10,000 people in the United States and 3.58 per 10,000 people in the EU.

Pulmonary Hypertension in IPF

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) frequently develops as a complication of IPF. Its reported prevalence ranges from 8–15% in the early stages to over 60% in patients undergoing evaluation for lung transplantation.

The presence of PH in patients with IPF is particularly concerning, as it is a strong predictor of both increased morbidity and mortality. Pulmonary hypertension compounds the challenges of IPF by further reducing physical capacity and significantly worsening survival outcomes.

Current Treatment Landscape and Unmet Needs

There is currently no cure for IPF, and life expectancy after diagnosis is typically 3 to 5 years. Treatment options remain limited, with only two approved antifibrotic medications: nintedanib and pirfenidone. Both therapies have been shown to slow the decline of lung function and disease progression. However, they are often associated with side effects and tolerability issues, and they do not halt or reverse the underlying fibrosis.

Lung transplantation remains the only treatment that can significantly extend survival in IPF, with an average post-transplant survival time of 4–5 years. However, the limited availability of donor organs and the risk of chronic rejection restrict access to this option for many patients.

Furthermore, these antifibrotic treatments have not been studied extensively in patients with pulmonary hypertension due to IPF. Emerging evidence suggests that standard antifibrotic therapy does not improve prognosis in IPF patients with pulmonary hypertension. Notably, IPF patients with elevated baseline pulmonary arterial systolic pressure (PASP > 50 mmHg) treated with pirfenidone or nintedanib had significantly worse survival outcomes.

As a result, there remains a critical unmet need for new, disease-modifying therapies that offer both effective management of fibrosis and better safety and tolerability profiles, especially in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Addressing this need could significantly improve daily functioning, quality of life, and survival for people living with IPF.

Rare thrombotic indications

Rare thrombotic disorders are a group of uncommon but potentially life-threatening conditions characterized by abnormal blood clot formation in veins or arteries. Unlike more common thrombotic events such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE), these disorders often involve unusual locations, genetic predispositions, or autoimmune mechanisms.

Examples of rare thrombotic disorders include:

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS)

- Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia (HIT)

- Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP)

Clinical challenges and unmet needs

These conditions often present with non-specific or atypical symptoms, making diagnosis challenging and frequently delayed. Specialized diagnostic tests, such as ADAMTS13 activity testing in TTP or anti-phospholipid antibody testing in APS, are often required to confirm the diagnosis.

Despite being rare, these disorders carry a high clinical burden due to their acute presentations, risk of relapse, and potential for serious complications. While treatment options have expanded over recent years, the therapeutic landscape remains fragmented.

For most rare thrombotic disorders, standard of care involves anticoagulant therapies, which, although effective in many cases, carry a significant risk of bleeding. Moreover, anticoagulants may not fully address the underlying disease mechanisms in these conditions.

There is therefore a clear unmet need for new treatments that can prevent thrombosis effectively without significantly increasing bleeding risk. A safer and more targeted therapy could transform the current treatment approach and significantly improve outcomes for patients with these rare, high-risk clotting disorders.

Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS)

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is a systemic thrombo-inflammatory disorder characterized by vascular blood clots (thrombosis) and/or pregnancy complications, linked to the presence of persistently elevated antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs).

APS can occur as a primary condition, meaning it appears on its own, or secondary to other autoimmune diseases, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In rare cases, patients may develop catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS), a severe form of APS where blood clots form in multiple small blood vessels across different organs, leading to multi-organ failure and a high risk of mortality.

Pathology and clinical impact

The underlying pathology of APS is driven by immune cell and platelet activation. Antiphospholipid antibodies stimulate immune responses, triggering NETosis (the release of neutrophil extracellular traps into the bloodstream) and platelet-mediated clot formation. This process results in clotting in microvasculature, contributing to organ damage and dysfunction.

A hallmark feature of APS is a decrease in cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels within neutrophils, leading to further immune cell activation and the promotion of clot formation.

The estimated global prevalence of APS is around 50 per 100,000 people, with significant differences observed between males and females.

Current Treatment Landscape and Unmet Needs

Currently, the mainstay of APS treatment is anticoagulant therapy, including:

- Aspirin

- Warfarin or other vitamin K antagonists

- Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) such as rivaroxaban in select patients (Xarelto)

While these therapies are effective in about 80% of cases for large-vessel thrombosis prevention, they do not protect against clotting in the small blood vessels (microvasculature). As a result, patients remain at risk for organ dysfunction and failure despite ongoing treatment, in addition, to the increased risk of bleeding.

There remains a significant unmet need for new therapies that can address both large and small vessel thrombosis, modulate the underlying immune activation, and offer safer, more effective protection against disease progression in APS.